Making Sense of Cranial Osteopathy: Osteopathy and Evidence

by Dr Mandy Banton | 2021

PhOst | Article 1 · Making Sense of Cranial Osteopathy: Osteopathy and Evidence

In this article, I discuss the challenge to osteopathy posed by the advent of Evidence-Based Medicine in the 1990s. I analyse some of the contradictions inherent within the EBM model and explain how it is evolving to take more account of the experience of patients and the nature of practice. I argue that osteopathy can and should participate in generating an evidence-base illustrating how we help our patients, but that this should be through creative and progressive investigations into the nature of practice, using contemporary research paradigms and methodologies.

Evidence-Based Medicine

EBM was a movement that emerged from a critical review of mid twentieth-century clinical practices in western medicine. Its early developers, David Sackett and Gordon Guyatt, proposed the use of scientific methods – such as statistical analyses of epidemiological data, guidelines based on randomised controlled trials, and systematic reviews of what was considered to be the most reliable, trustworthy evidence available – in order to inform clinical decision-making at both individual and population-based levels.

The advent of EBM represented a fork in the road for western medicine, when a consensus developed that – for ethically utilitarian reasons (i.e., trying to offer the best medicine to the greatest number of people) – diagnostic and treatment pathways should be rationalised and standardised. At this point, western medicine became anchored to the scientific methods that worked well for population studies, public health and epidemiology. These methods were based on mathematical modelling and were designed to provide doctors with syntheses of research, in support of clinical decision-making.

EBM has attracted criticism from clinicians, philosophers, sociologists and patient groups, but it has become embedded within western medicine and healthcare systems across the globe. One reason for this is that policy-makers and funders of healthcare identified the need to systematise the provision of medical pathways of diagnosis and treatment during an era in which biomedical research was beginning to proliferate. The idea was that the provision of medicine would be subject to checks and balances, so that none of the main stakeholders (pharmaceutical companies, governmental bodies, insurance providers, individual clinicians and their professional associations, nor patient campaigning organisations) could dominate medical policy and provision without accountability. Physicians, consultants and hospital administrators would follow clinical pathways and guidelines, synthesised by independent volunteer researchers, such as those who work for the Cochrane Collaboration.

Challenge of EBM for Complementary, Alternative and Allied Health Professions

Whatever our views on western medicine and its relationship with osteopathy, EBM is the inescapable context of osteopathic practice in most healthcare systems across the world. Some osteopaths have embraced EBM, its principles and its methodologies with enthusiasm. Others have shown “quiet dissent” (Figg-Latham & Rajendran, 2017), finding EBM a threat to their sense of professional identity. But when osteopaths – or other complementary, alternative and allied health professionals – have tried to respond to the EBM challenge, it has often been with disappointing results. It has been difficult to demonstrate evidence of safety and effectiveness of non-pharmacological / non-surgical treatment interventions using so-called gold-standard research methodologies. The reasons for this are complex and varied, and the subject for a separate article. Yet, regardless of what “the evidence shows”, osteopaths operating in jurisdictions where the profession is regulated are expected to practice in a way that upholds the principles of EBM.

For example, in the current UK Osteopathic Standards of Practice, within section C (Safety and quality in practice), and under the heading C1 (“You must be able to conduct an osteopathic evaluation and deliver safe, competent and appropriate care to your patients”), we find sub-heading 1.4; osteopaths should have the ability to:

1.4 develop and apply an appropriate plan of treatment and care; this should be based on:

1.4.1 the working diagnosis

1.4.2 the best available evidence

1.4.3 the patient’s values and preferences

1.4.4 your own skills, experience and competence

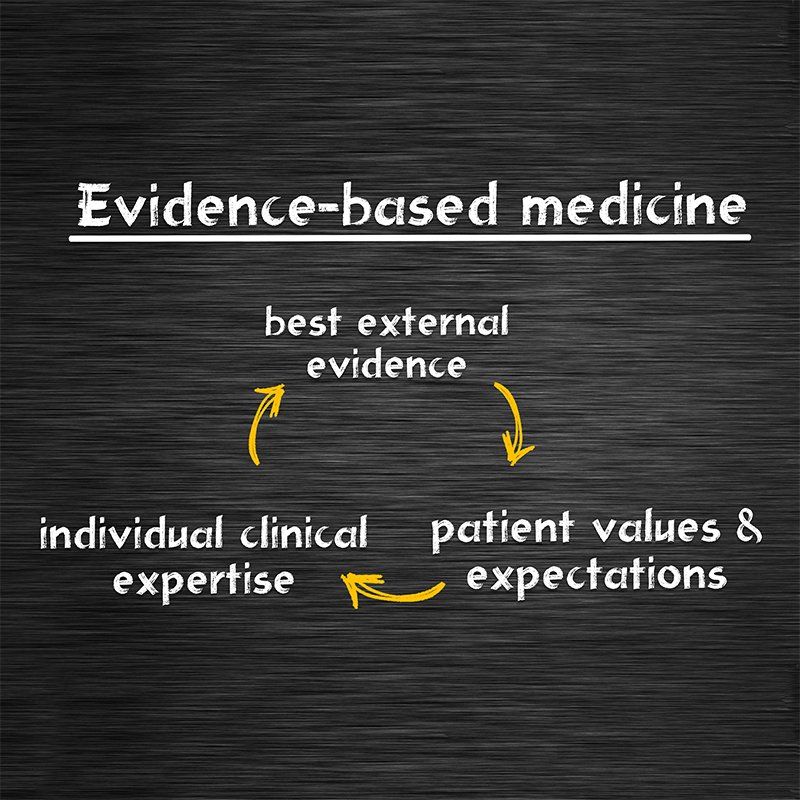

These last three points reflect the principles of EBM, shown in Figure 1.

On the face of it, this seems like a workable model, with room to balance the experience of the clinician with the expectations of the patient. However, the version of EBM that has come to predominate within western medicine (and has consequently influenced the research agenda for complementary, alternative and allied health professions) has tended to privilege “evidence” over “expertise” and “patient values”, as I discuss below.

Philosophical Tensions within EBM

Even a superficial examination of the relationship between the three principles of EBM will highlight their incompatibility. The best available evidence emerges from the post-Enlightenment tradition which holds that independently verifiable facts about an objective world can be proved by scientific methods. Clinical expertise and patient values, however, belong to different realms of knowledge: clinical expertise to the domain of phronesis (practical wisdom); and patient values to social, cultural and ethical forms of understanding. Proponents of EBM often fail to acknowledge that alternative sources of knowledge might have relevance for the practice of medicine, and tend to assert that the scientific paradigm reigns supreme.

A consequence of this is that there has also been a failure to properly account for the role of the therapeutic alliance between the patient and the practitioner in clinical encounters. The relationship between the patient and the clinician ends up being dismissed as part of the “placebo effect” or downplayed as a “contextual effect” of care (i.e., something of an epiphenomenon). Patients’ experience and values are relegated as non-essential aspects of medicine, with far greater emphasis placed on the acquisition and recording of consent than on a collaboration in the service of truly patient-centred care. In my own doctoral research project, “Making Sense of Cranial Osteopathy”, I was able to investigate the fascinating area of the healing dynamic between cranial osteopath and patient using a philosophical methodology called phenomenology. I was able to show that, far from being a side-concern of treatment (and as many osteopaths would attest), the therapeutic alliance was germane to the beneficial effects of osteopathic care.

Reform of EBM

EBM may be the best strategy for medical decision-making and policy roll-out at a population level –with examples being the evaluation and implementation of the Covid-19 vaccination programme, and the Recovery Trial. But even if we accept that the health crisis represented by Covid-19 is best placed within the purview of orthodox medicine (and I acknowledge that there are good arguments against this idea), what about individualised clinical care provided in one-to-one contexts by GPs, osteopaths and other allied health professionals? Must our practice be based on diagnostic and treatment guidelines, even when these seem to contradict what we and our patients “know”?

One way of looking at this is to contrast the view from the top of the mountain, which philosopher Donald Schön called the “high, hard ground” of theory and technique; and the first-person experience of practice, down in the “swampy lowland” (Schön, 1983, p. 42).

EBM is part of the landscape in which we practice; but decisions about how we practice, I argue, should be informed by research that explores real-world experience of health, illness, diagnosis and treatment – that is true to life and represents the understanding and lived experience of patients and practitioners.

When I began my research project, I wasn’t at all sure how I would be able to investigate the phenomenon of cranial osteopathy in a way that would be both academically rigorous and also sympathetic to its philosophy. I was fortunate to be mentored by the late Professor Stephen Tyreman, who introduced me to phenomenology. From a phenomenological perspective, patients are individuals who should always be viewed in the context of their own “Life-world”, as people with agency, dignity and understanding of their circumstances. And it is the phenomenological perspective of practice and the lived experience of patients that underpins the current reform of EBM, which has been advanced by influential voices such as Professor Michael Loughlin, Rani Lill Anjum and Elena Rocca (philosophers), Roger Kerry (philosopher and physiotherapist) and Trisha Greenhalgh (academic and GP).

Within the scientific discourse of EBM, it is very difficult to “prove” that the interventions offered within healthcare practices such as osteopathy have value for patients and are “safe and effective”. With the new model of EBM, or Evidence-Based Practice, new frontiers have opened up, and there has been a call for creative methodologies such as phenomenology to explore Life-world experiences. For example, Michael Loughlin expresses the view, “we do not understand health and illness or the purpose and nature of health care, unless we ground that understanding in the everyday experience of those who have to live with illness” (Loughlin, 2016, p. 462). Phenomenology provides a rationale and a strategy for investigating the lived experience of patients and practitioners (i.e., attempting to understand their experience according to their own account, and on their own terms), as they try to make sense of their experience of illness and healthcare. EBM can expand to incorporate these concerns; no longer is objective proof is the only goal of healthcare research; illuminating experience is now also on the agenda.

This new model of EBM is one that applies to practice, rather than population-level medicine, and it is far more sympathetic to whole-person-centred healthcare practices such as osteopathy, where practitioners spend time with their patients, listen to their stories, care about their experiences, and collaborate with them in enabling and holistic ways. The metaphor of ceramics production helps me to think about the differences between population-level medicine and healthcare practice. In EBM, there are assumptions about the uniformity of patients, and an industrial, one-size-fits-all approach to, e.g., the mass prescription of statins. In a healthcare practice, by contrast, there is a presumption that each individual patient comes with their unique causal story, and the practitioner relies on their practical wisdom to help the patient.

My Research: Making Sense of Cranial Osteopathy

Having been introduced to phenomenology, and reading some of the works of its leading proponents, Martin Heidegger and Maurice Merleau-Ponty, I set about investigating cranial osteopathy as it is experienced and understood in real-world practice. I outlined the research process in last year’s edition of the SCCO Magazine and look forward to illustrating the project and its findings in the 2021 Rollin Becker Memorial Lecture on 27th November 2021.

The main themes arising from my study, in which I interviewed four Fellows of the SCCO and a patient of each of theirs, about their understanding and experience of cranial osteopathy, were:

Making Sense of Sense-Making

Cranial osteopaths and their patients did not doubt the significance of the fine-grained, sensory experience of osteopathic palpation and the interoceptive, embodied communication which flowed between them during assessment / treatment. In fact, they adopted a receptive, phenomenological stance towards this aesthetic experience, realising that it plays an important part in understanding the nature of the patient’s ailment.

Metaphors for Mechanisms

The subtle, aesthetic feelings involved in cranial osteopathic assessment and treatment revealed embodied (unverbal) metaphors for the experience of the signs of dis-ease, distress and unhealth, and of the change towards ease, function and health. These were converted through language to verbalised metaphors, speaking, for example, of integration, alignment, and the whole body breathing.

The Meaningful Osteopathic Relationship

Both patients and osteopaths understood that the therapeutic relationship is at the heart of the transformation towards health. The relationship is one of resonant attunement and of collaboration, in which both parties work together to understand the causes of dis-ease, so that the underlying rhythm of health can be unconcealed.

There is far more to say about the language and concepts I use, what I mean by them, and where they might lead us. I look forward to explaining and illustrating the phenomenological model of osteopathic practice that emerged from my analysis, and its potential implications, at the

Rollin Becker Memorial Lecture. I also look forward to a discussion about the significance of this research project for osteopathic enquiry and education, and the way ahead for establishing an evidence-base for cranial osteopathy.

Implications of Phenomenological Research

It is early days yet, but with Trisha Greenhalgh calling in the British Medical Journal for the establishment of an Institute of Patient-Led Research, and research projects involving phenomenology (and other creative methodologies such as auto-ethnography), we can perhaps envision a future in which the real-world concerns and experience of individual patients – and the practical wisdom of healthcare practitioners – becomes embedded as standard within osteopathic and medical research.

References

Anjum, R., Copeland, S., Elena, R., eds (2020) Rethinking Causality, Complexity and Evidence for the Unique Patient. Springer.

Figg-Latham, J. and Rajendran, D. (2017) ‘Quiet Dissent: the attitudes, beliefs and behaviours of UK osteopaths who reject low back pain guidance – a qualitative study’, Musculoskeletal Science and Practice, 27, pp. 97-105.

Greenhalgh, T., Howick, J. and Maskrey, N. (2014) ‘Evidence based medicine: a movement in crisis?’, British Medical Journal, 348(4), g3725–g3725.

Greenhalgh, T. (2015) ‘Real v Rubbish EBM’, available at:

Greenhalgh, T. et al (2015) “Six ‘biases’ against patients and carers in evidence-based medicine”, BMC Medicine, 13, 200.

Loughlin, M., Fuller, J., Bluhm, R., Buetow, S. and Borgerson, K. (2016) ‘Theory, experience and practice’, Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 22, pp. 459-465.

Martini, C. (2021)

‘What “evidence” in Evidence-Based Medicine?’

Topoi, 40, pp. 299-305.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1962) Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Colin Smith. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968) The Visible and the Invisible. Edited by C. Lefort; translated by A. Lingis. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Mulhall, S. (2005) The Routledge guidebook to Heidegger’s ‘Being and Time’. 2nd edn. London and New York: Routledge, Taylor and Francis.

Newell, D., Lothe, L. and Raven, T. (2017) ‘Contextually Aided Recovery (CARe): a scientific theory for innate healing’, Chiropractic & Manual Therapies, 25(1).

Pattani, R. and Straus, S. (2020) ‘What is EBM?’, BMJ Best Practice.

Schön, D. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner. New York: Basic Books.

Sheridan, D. and Julian, D. (2016) ‘Achievements and limitations of Evidence-Based Medicine’, Journal of the American College of Cardiology, vol. 68 (2), pp. 204-213.

Zimmerman, A. (2013) ‘Evidence-Based Medicine: A short history of a modern medical movement’, Virtual Mentor, 15(1), pp. 71-76.